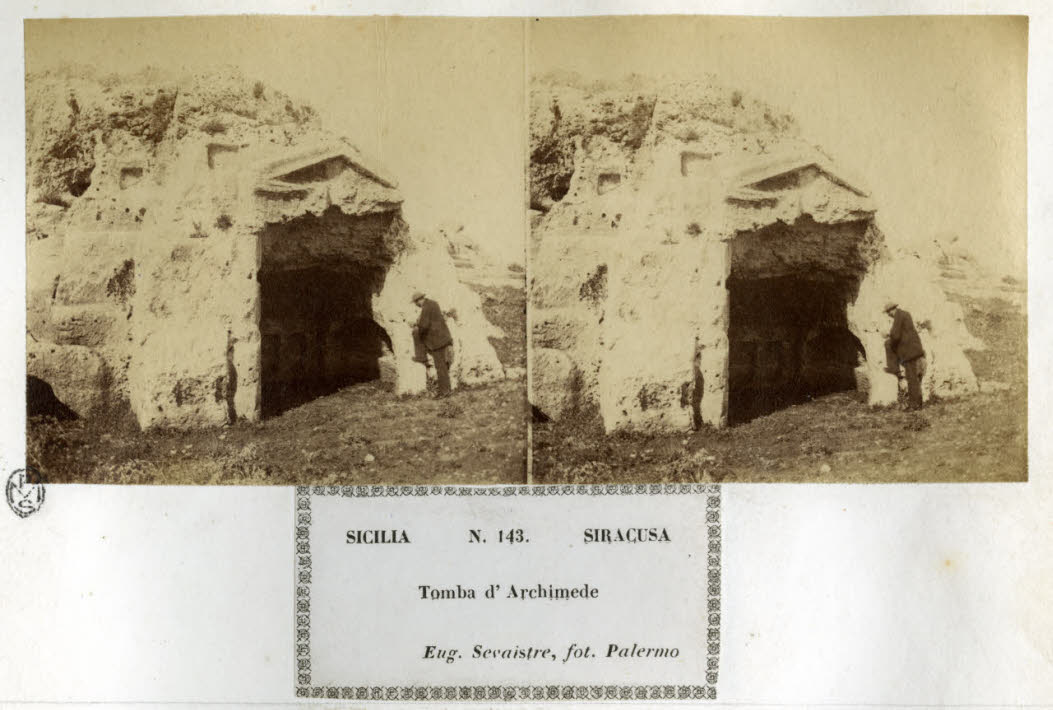

One of the painters who contributed more than any other to bringing us closer to the ancients from a point of view that guarantees emotions before thoughts is the German Carl Anton Rottmann (1797-1853). One of his oil paintings depicting the Tomb of Archimedes, for instance, shatters the entire previous figurative tradition and solves a problem of identification that had been going on since time immemorial.

Rottmann imagines an almost deserted setting, with an abandoned ruin in a landscape, with only a small house and a farmer beside it. The sepulchre is accessed through a portal that still has a pediment supported by two columns, but everything seems swallowed up by superfetations, vegetation and clouds. With a scornful immediacy that is wholly romantic, the artist imagines, in short, what could no longer be tackled armed only with the philologist's toolbox. Scholars and painters had been fantasising about the subject for centuries. First, to represent Cicero finding the tomb of Archimedes, one could rely on a precise passage from the Tusculanes (V, 23, 64-66). The orator from Arpino recalls having discovered the tomb - a small column that was surmounted by a sphere and a cylinder - by rescuing it from brambles and oblivion, in the necropolis of Syracuse outside the Agrigento gate. Tommaso Fazello (1498-1570), the prodigious Dominican humanist from Sciacca, had renounced the undertaking:

‘Not only is there no vestige of this burial today, but we do not even know the place where it was’.

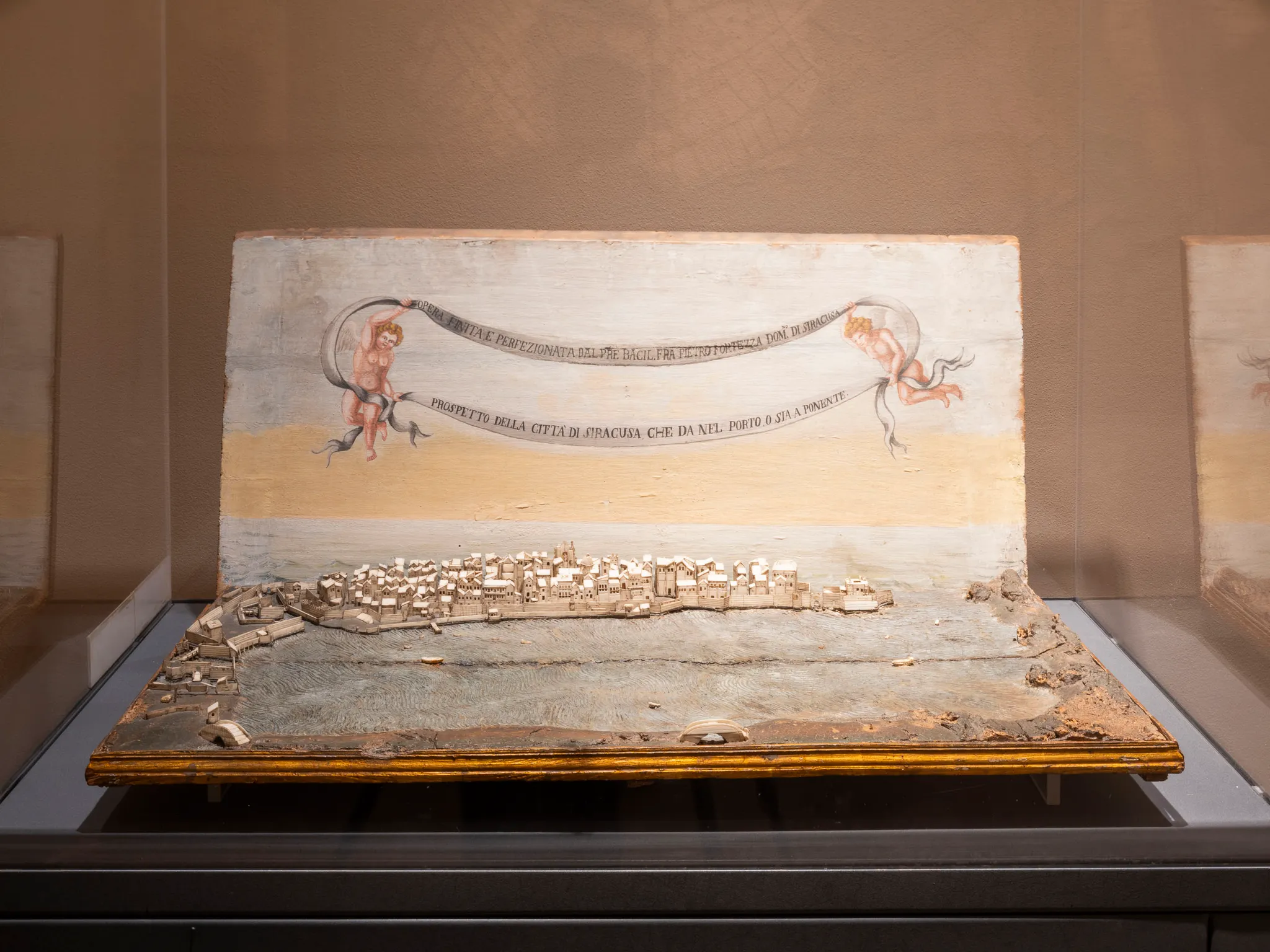

In 1813, the antiquarian Giuseppe Maria Capodieci had prudently linked sources from the Roman period with two columbaria in the Necropolis of the Groticelle, now inside the Neapolis Archaeological Park, which have an aedicule entrance (Ancient Monuments of Syracuse, II, pp. 128-130). This was enough to invent a tradition, which reaches beyond Rotmann's painting to the age of photography.

In the neoclassical age, the scene of Cicero's discovery of the tomb appealed even more than the possible site, to be researched using the skills of topographers and archaeologists. Thus it happened to see great painters such as Pierre-Henri Valenciennes or Benjamin West try their hand at the theme. The former immerses the scene in an ideal landscape, where the city with its temples lies in the background and is bathed by the sea. Instead, in the foreground, statues of deities with altars still in use emerge among broken trunks and craggy cliffs and, on the right, the discovery of a tomb takes place.

Benjamin West, an American painter enjoying a certain fortune in Europe, imagines instead the Syracusans shrewdly confronting Cicero who disturbs their spirits by discovering the tomb of the great scientist. They had forgotten about him: and now it was the turn of a new generation to rediscover the fathers of buried worlds.