“You have often heard that Syracuse is the greatest Greek city, and the most beautiful of all. Its fame is not usurped: it occupies a very strong position, and moreover it is very beautiful from whatever direction one approaches it, whether by land or by sea, and it has two harbors almost enclosed and embraced by the buildings of the city. These harbors have different entrances, but they join and flow together at the other end. At the point of contact, the part of the city called the island, separated by an arm of the sea, is however reunited and connected to the rest by a narrow bridge. The city is so large that it is considered as the union of four cities, and very large ones: one of these is the already mentioned "island", which, surrounded by the two harbors, extends to the opening that gives access to both. On the island is the palace which belonged to Hiero II, now used by the praetors, and there are many temples, among which by far the most important are that of Diana and that of Minerva, rich in works of art before the arrival of Verres. At the end of the island is a spring of fresh water, called Arethusa, of extraordinary abundance, full of fish, which would be completely covered by the sea, if a stone dam did not prevent it. The other city is called Acradina, where there is a very large forum, beautiful porticoes, a prytaneum rich in works of art, a very large curia and a notable temple of Olympian Jupiter; the rest of the city, which is occupied by private buildings, is divided along its whole length by a broad street, intersected by many cross-streets. The third city, called Tycha because there was an ancient temple of Fortune in it, contains a very large gymnasium and many temples: it is a very elegant district with many houses. The fourth is called Neapolis (new city), because it was built last: in the highest part of it is a very large theater, and also two important temples, of Ceres and Libera, and the statue of Apollo called Temenite, very beautiful and large, which Verres, if he could, would not have hesitated to take away”.

With these very famous words, Marcus Tullius Cicero draws an immortal portrait of Syracuse.

"Syracuse is a great palimpsest, a site and a space that time and history have helped to build, destroy, rebuild and hide from the sight of posterity".

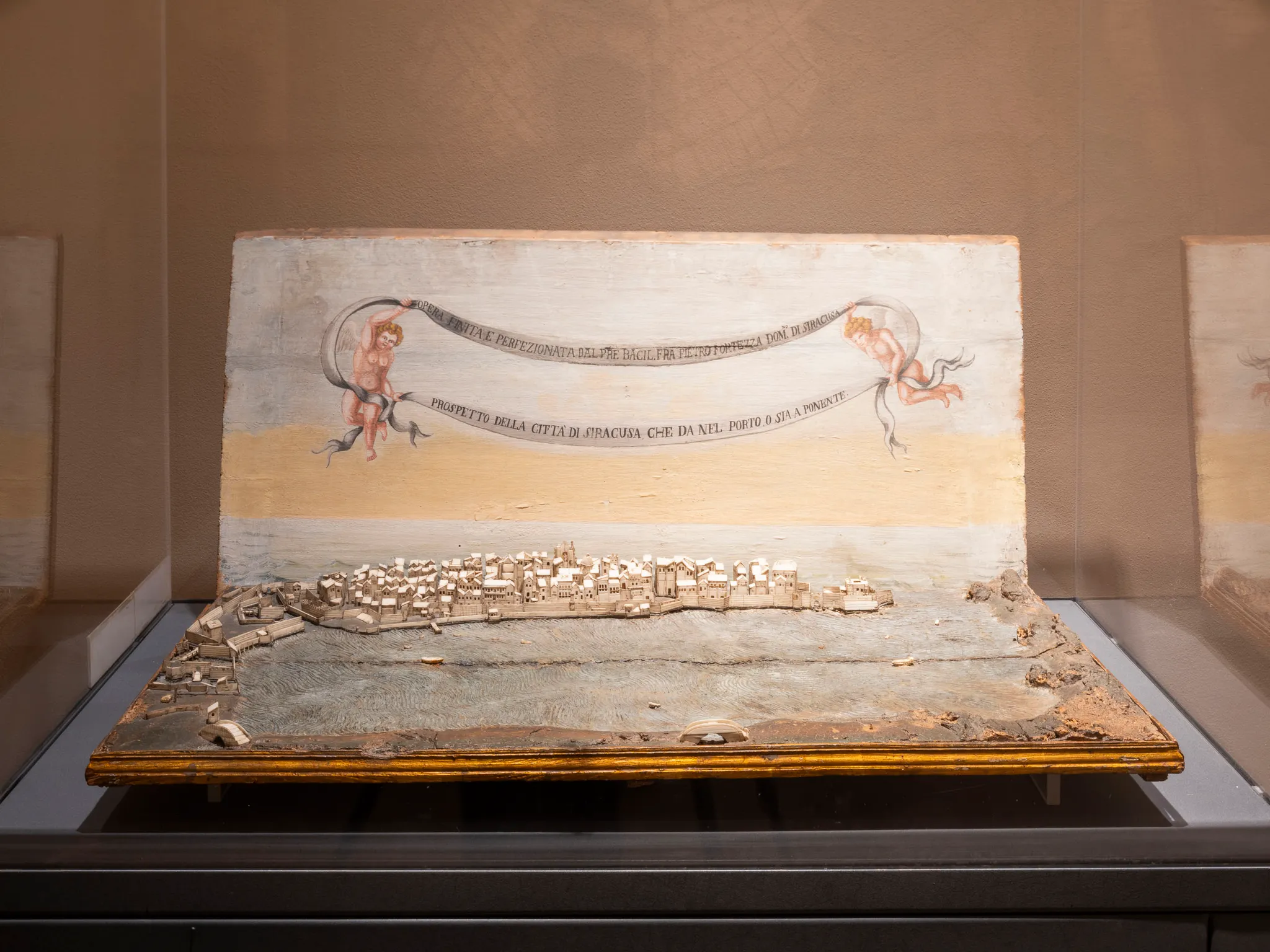

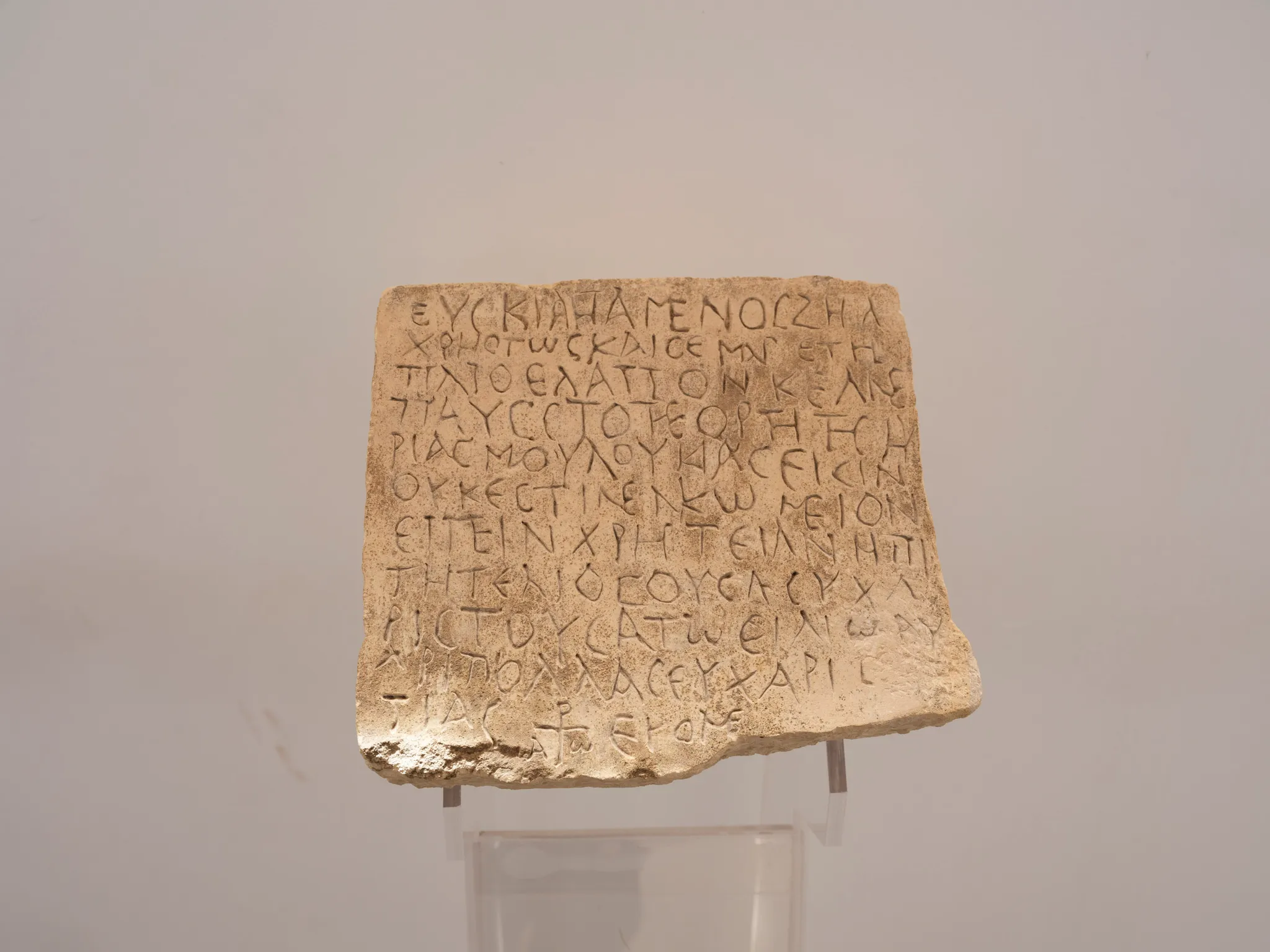

"The reflection on the past of Syracuse passes through the narration of a story that highlights its continuity and discontinuity, history and chronicles that materialize in the documents of its past, in its iconography and in its cartography, powerful vehicles of the collective imagination. The images are documents in which one can "read" the various seasons that have lived and transformed the ancient Greek site, leaving prodigious traces of the urban stratifications and the changing identities". These are the evocative words of L. Doufour, professor at the Sorbonne and adoptive citizen of Ortigia.

Syracuse is a Greek colony. Pausanias says that the oracle of Delphi, sending Archias of Corinth to found Syracuse, recited these verses to indicate to the colonists the site of the new homeland:

"Ortygia is there in the dark sea immersed to guard Trinacria, where Alpheus flows and mixes with the water of Arethusa".

According to the myth, the nymph Arethusa, to escape Alpheus, threw herself into the sea and transformed herself into a sea current. Alpheus, to chase and reach his beloved, transformed himself into a river, flowed into the sea near Olympia and, having crossed the sea without getting lost and without confusing its fresh waters with the salty sea, finally managed to join Arethusa at the exact point where the spring that in Ortygia bears the name of the girl springs. The story of Arethusa, her literary and iconographic fortune, is closely linked to the mythopoetic production of the Magna Graecia area and chronologically takes place between the 6th and 5th centuries.

The erotic impulse of the river god who, following the impetus of love, crosses the sea and reaches Sicily tells the story of the founder of the Doric colonists who cross the sea to re-establish the Greek profile of their homeland in a new City: the myth thus transcribes the victorious migration that leads Greek civilization to flourish in its highest expression right in Sicily. The journey from Olympia to Syracuse, favored by the myth, therefore has an extraordinary historical and cultural significance.

The motherland of Syracuse is Corinth, which will be the great ruler of the seas throughout the archaic age. Its vocation for colonization and expansionism overseas matures in very ancient times, at the time in which the City is dominated by the oligarchy of the Bacchiadi lineage. A nascent seafaring and entrepreneurial class then took its first steps, aided in its economic take-off by the very fortunate geographical position of the City which – already from the middle of the 8th century – constituted a primary port and an obligatory connection point for all goods in transit between the East and the West. Corinth has, in fact, two large ports – Lecheo and Kenchre – which overlook, respectively, the Corinthian and Saronic gulfs. Ports that over time will be connected to each other, by land by a wooden track, by a díolkos, which will allow ships to be transhipped from sea to sea for the entire length of the Isthmus.

As Lorenzo Braccesi reminds us

"It is therefore not surprising that Corinth was able to extend its range of action in distant areas, especially towards the west. Where it founded the powerful colonies of Corcyra and Syracuse on the coast of Epirus and in Sicily, which in turn were destined to become metropolises of further settlements. In short, it supplanted the expansionist primacy of the same metropolises of Euboea and the push for colonization transformed it into a city where a ceramic industry flourished, destined for export in exchange for raw materials and slaves. In a city where shipyards were built - with cutting-edge technical solutions - capable of launching the first triremes of the Hellenic world which, according to Thucydides, were built by a genius of shipbuilding, Aminocles of Corinth, and had little to envy those of the following centuries. The Triremes were light boats with propulsion ensured by three rows of oarsmen in addition to the usual and unwieldy rectangular sail. They were armed with a rostrum, with a wooden spur covered in bronze, and the lateral bulk doubled, increasing their stability, with the oars extended outboard. In fact, for centuries they constituted the main vessel of all the fleets of the Mediterranean: not only Hellenic, but also Phoenician, Carthaginian, Lydian and Carian.”

Syracuse was founded by Archias, in 734 BC, who came from Corinth, about the same time as Naxos and Megara. It is said that Myscellus and Archias went to Delphi together: to both of them, who questioned him, the god asked whether they preferred wealth or health; Archias chose wealth, Myscellus health. Then he granted to one to found Syracuse and to the other Croton. Thus it happened that the Crotonians inhabited a healthy city and the Syracusans came to such wealth. Sailing towards Sicily, Archias landed at Cape Zephyrion and “having met some Dorians who had come there on their way home from Sicily, after having separated from the founders of Megara [Iblea], he took them with him and together with them founded Syracuse"...

Archias (Ἀρχ́ιας) is a speaking name that would seem to denounce the role of ‘guide’, or the destiny of archegete, of the character, as well as his aristocratic origin.

The oldest foundation of Syracuse concerns exclusively the island of Ortigia, equipped with an abundant source of fresh water and two landing places, destined, over time, to become very well-equipped ports, both military and commercial. Especially when the island - as Thucydides recalls - will be connected to the coast by an artificial pier that will further delimit them. Later, becoming increasingly populous, Syracuse "no longer surrounded by water" also extends onto the nearby mainland, occupying the triangular plateau of Epipoli where its most populous neighborhoods will arise.

In the 5th century, the "tyranny" of Hieron flourishes in Sicily: the prince's court is a center of magnificence and culture, the great economic means promote the architectural flourishing of cities and temples, its military power contrasts the Phoenician hegemony of Carthage on the sea, making Syracuse the bulwark of Western Greekness. In Syracuse, a theatre more imposing than the theatre of Dionysus in Athens was built, and for that theatre Aeschylus himself, the greatest tragedian of the time, came from his homeland to stage his tragedies. In the last quarter of the 5th century, during the battles between the Greek cities that Thucydides called the Peloponnesian War, Syracuse inflicted a resounding defeat on the Athenian army that contributed to the definitive outcome of Athenian hegemony.

At the beginning of the following century, Syracuse had another period of splendor under the principality of Dionysius II: the monumental remains of Castello Eurialo, the only Greek fortress of these proportions that has been preserved in the entire Mediterranean area, bear witness to the power of the city.

Plato is a guest at the court of Dionysius, and it is precisely in the Syracusan period, in the reconstruction of the internal chronology of Plato's works, that the Republic is placed, the dialogue on the utopia of the Ideal State and the philosopher-kings. In book X of the Republic, Plato also tells a "myth", a figurative story, destined to leave its mark on all the metaphysics of the Western tradition. It is the "myth of the cave", according to which mortals are, without being aware of it, chained at the bottom of a tunnel, turned to see only reflected images projected on a wall from their backs. Only the wise philosopher becomes aware of the condition of imprisonment, frees himself from the chains and, with great difficulty, climbs back up towards the Sun of Truth, exposing himself to the risk of being dazzled by it. The setting of the "myth of the cave" could have been influenced by the chthonic shadows of the tunnels of the hypogea that run under Ortigia, in the heart of the City.

And until the middle of the 4th century, the profile of the nymph Arethusa appears on Syracusan coins as the symbol of the city, with dolphins darting through the locks of her hair.

Even in its period of maximum splendor, in which the flourishing Sicilian city prevails even over the powers of the mother country now in decline, the princes of Syracuse reaffirm, with the mythical allusion to the nymph loved by Alpheus, the floating and mobile root of Greek civilization united from one shore of the Mediterranean to the other by the water of the sea.

Fernand Braudel on the Greek essence of Syracuse in one of his visionary writings, poses a fascinating and incapacitating question: "what would have happened to Italy if Alexander, neglecting Asia, had directed his expedition against the West?" To a question like this the answer will always be that it is useless to rewrite history.

But we cannot resist the temptation to imagine Syracuse that, with Alexander, would have become the metropolis of the Inner Sea, of a Greek empire that conquered both Rome and Carthage, extending a direct Hellenism to us, Westerners, without the intermediation and filter of Rome. A war that did not take place is still a lost war. The greatness of the Inner Sea, already at that time, is played out, whether we like it or not, in the place that acts as a hinge between the two Mediterraneans.

Sicily is another Greece, and Syracuse, in the 5th century, at the height of its splendor presents itself as a second, magnificent Athens, which has nothing to envy of the cultural capital of the mother country.

Sicily, Syracuse, in the time of its origins is thought of as Western Greece: but this Greek value, and the political and cultural importance of the powerful Sicilian city states in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, is not fully perceived in contemporary sensibility, and is often misunderstood even by potential cultured travelers.

If the journey to Greece is, to this day, a fundamental stage in the cultural and aesthetic formation of the European individual, the thousands of young people and travellers who crowd the historical-archaeological sites of Greece rarely seek in Sicily the second, necessary, stage of their formative journey, connecting the two experiences. Syracuse was therefore the cultural epicentre of Sicily in the classical age, but its history does not end there.

In the heart of Ortigia stands the Cathedral of the City; it is accessed through a baroque façade which however is soon discovered to be only an illusory prospect that contains a treasure, another marvel: the church, one of the first basilicas of the Christian era, was built in the 5th century AD on the Doric temple dedicated a thousand years earlier to the goddess of the City, Athena. And behind the 18th century façade is the wonderfully intact Greek Temple: the Christian re-semanticization saves the pagan architecture from destruction and oblivion and delivers it to tradition, giving new life to the sacredness of the ancient place. The reuse of the temple of Syracuse is an extraordinary example of the mechanism of material and symbolic reuse that, in the first centuries of our era, decided the victory of Christianity, and on which great European scholars such as Dumezil and Mircea Elide have written memorable pages: the protective and defensive functions of the ancient Athena-pallàdion are transferred, starting from the 5th century AD, to the images of Mary and the patron saints of the cities.

And if the most important temple of Ortigia was dedicated to Athena, the goddess with the shining gaze who watches over and protects the City, around the virgin Lucia, martyred in 303 AD, the legend of the luminous eyes of the saint arose, torn out according to tradition before the martyrdom. Saint Lucia thus promptly replaces the pagan goddess in the function of pallàdion, talisman and protective simulacrum of the City.

Syracuse, which had been in the past "the Athens of the West", in the Middle Ages, in the centuries in which Rome sank into degradation and oblivion, was awarded the title of western capital of the Byzantine Empire. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, Syracuse confirmed its role as a bridge city between East and West, but with this further dislocation of perspective, now centered on Constantinople, the erratic nature of Sicilian identity was also reaffirmed. Syracuse was restored to centrality and regained capital importance in the 13th century.

Frederick II found in fact in the topography of the City suspended between land and sea, between north and south, between East and West, an ideal center of his imperial project in which a new geopolitical idea was relaunched that has its fulcrum in the Mediterranean and fruitfully intersects the classical and European tradition with the technical, literary, artistic and philosophical wisdom - of the Arab shore. And Syracuse once again became, as it had been in the times of the Greek "tyrants", the seat of a court in which politics and law translate into an aesthetic instance of the highest profile and give life to an extraordinary, yet ephemeral, experimentum mundi.

In the Renaissance inaugurated by Frederick two centuries before the 15th century, jurists, architects, poets and troubadours, philosophers and artists, contributed to building a world project that made the Emperor's political fantasy come true: they translated the revolutionary intuition of the Stupor Mundi into verse, laws, stone and music.

The strong and shining sign of the Frederick imprint is still visible in the powerful and graceful lines, in the harmonious spaces, in the play of light and shadow of the Castello Maniace, located on the promontory as a bastion on the southern side of Syracuse. The last season in which Syracuse is the protagonist is the century of the Baroque: between the 17th and 18th centuries, following one of the many catastrophes that dot the history of Sicily and recall the restless and volcanic nature of this land, Syracuse and its province find themselves once again at the center of a great experiment of artistic and cultural rebirth.

The sign of the Baroque calls the matter to correspond to a philosophical thought of unprecedented intensity, to translate into forms the ideas of presence and absence, of being and becoming, of form and event; but that style in this land is mixed with the warm colors of the stones, comes to terms with the softness of the materials, gives in to the sweetness of the forms that carry the legacy of a long tradition of mediation. And instead of abstruse, cold, alienating, excessive forms, the stylistic figure of the late Sicilian Baroque is warm and captivating: grace and not gravity and in place of density the wise lightness that marks the baroque face of the cities of the south east.